How many missed? Texas is second-worst in the nation for COVID-19 testing

Six times in three weeks, Marci Rosenberg and her ailing husband and teenage children tried to get tested for the new coronavirus — only to be turned away each time, either for not meeting narrow testing criteria or because there simply were not enough tests available.

All the while, the Bellaire family of four grew sicker as their fevers spiked and their coughs worsened. They said they fell one by one into an exhaustion unlike any they had felt before.

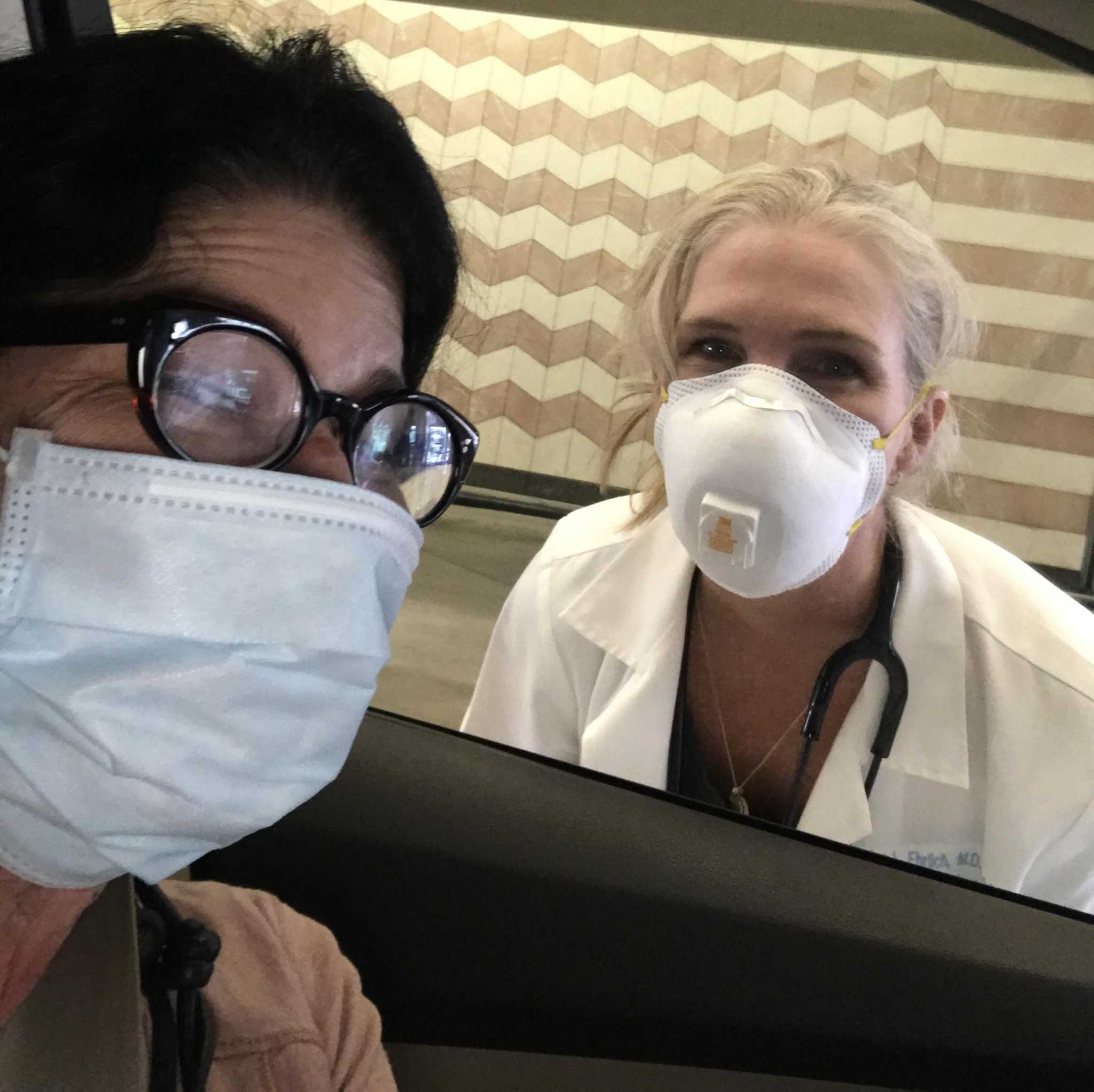

By March 18, Rosenberg was desperate and pleaded with her doctor for a test. Dr. Lisa Ehrlich, an internal medicine physician, told Rosenberg to pull into her office driveway. But Ehrlich warned Rosenberg, “I can only test one of you.” She swabbed her throat through an open car window. The result came back the next day: positive.

PANDEMIC EXPERT: Coronavirus will have 5 stages. We’re in stage 2 in Houston.

The rest of her family was presumed to be positive but untested – and thus excluded from any official tally of the disease.

As the number of confirmed cases of the potentially deadly virus continues to explode across the Houston region – tripling from 1,000 to more than 3,000 in just the past week – there is mounting evidence that the true scope of the disease here could be far worse than the numbers indicate.

A Houston Chronicle analysis of testing data collected through Wednesday shows that Texas has the second-worst rate of testing per capita in the nation, with only 332 tests conducted for every 100,000 people. Only Kansas ranks lower, at 327 per 100,000 people.

In cities across Texas — from Houston to Dallas, San Antonio to Nacogdoches — testing continues to be fraught with missteps, delays and shortages, resulting in what many predict will ultimately be a significant undercount. Not fully knowing who has or had the disease both skews public health data and also hampers treatment and prevention strategies, potentially leading to a higher death count, health care experts say.

In Houston, the nation’s fourth-largest city, officials worry that because the number of confirmed cases is lower than other major U.S. cities, the situation here may seem less serious. The federal government announced plans to cut 25 percent of its funding to help administer the city’s two testing sites and relocate six federal public health workers who help manage the sites.

Dr. David Persse, Health Authority for the Houston Health Department, protested the decision as a “monumental step backwards,” in a letter this week to Erica Schwartz, deputy U.S. surgeon general. On Thursday, the federal government agreed to extend funding for both the city and county testing sites through May 30.

The total testing volume for all four Houston-area sites, two run by city and two run by the county, has been capped at 1,000 people per day until Saturday, when federal officials pledged to double that capacity.

“Without robust testing we have no idea of our true numbers,” Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner has said. “You can look at the numbers we have (of confirmed cases) and multiply them by 10.”

Slow to start

As the pandemic’s march quickened, Texas was slow to ramp up testing.

The first confirmed case in Texas, outside those under federal quarantine from a cruise ship, was March 4, striking a Houston area man in his 70s who lived in Fort Bend county and had recently traveled abroad. By month’s end, the Houston area had more than 1,000 confirmed cases. A week later, the number had pushed past 3,000.

Yet it was not until March 30 that the rate of testing per 100,000 people in Texas topped 100. As of Wednesday, the state was testing 327 per 100,000, according to a Chronicle analysis of data from The COVID Tracking Project, which collects information nationwide on testing primarily from state health departments, and supplements with reliable news reports and live press conferences.

Twenty-six states in the U.S. are testing at least double the number of patients per capita as Texas, in some cases six times more. New York, for instance, is testing 1,877 per 100,000 people while neighboring Louisiana is testing 1,622 per 100,000. Even smaller states, such as New Mexico, are testing triple the rate of Texas.

Texas officials defended the state’s response.

“We’ve consistently seen about 10 percent of tests coming back positive, which indicates there is enough testing for public health surveillance,” said Chris Van Deusen, a spokesman for the Department of State Health Services, in an email, “If we saw 40 or 50 percent or more of test coming back positive, we’d be concerned that there could be a large number of cases out there going unreported, but that has not been the case.”

It is unclear if that is a reliable measure. Nearly 41 percent of New York tests were positive, the second-highest rate in the country. In Texas, about 9.4 percent of tests were positive — roughly the same as Washington state, where one of the largest outbreaks of coronavirus has occurred.

At a news conference this week, Gov. Greg Abbott downplayed any problems with testing. “The bottom line is whatever the source may be, we are seeing more testing achieved in the state of Texas,” he said.

The stakes for better testing could not be higher. Without widespread testing, experts said, it is impossible to fully quantify how many people have the disease and to identify hotspots. Public health officials have said they need to establish a large enough baseline to see patterns, deploy resources and ultimately calculate mortality rates.

As of Saturday, the number of confirmed cases nationwide had grown to more than 526,00 with more than 20,000 deaths. The number of deaths in Texas was 271.

Rural trouble to come?

In early March, when the national number of confirmed cases was just reaching triple digits, University of Texas researchers in Austin began examining the virus’ potential spread using models originally developed when the Zika virus swept the world in 2016.

In both instances, testing capacity was low and many who were infected never showed symptoms, which led to underestimates of the diseases’ true toll, said Spencer Fox, a research associate and data scientist at the university.

“We found that even if a county has only one or two cases,” said Fox, whose research is currently under peer review, “those cases likely signal that there is a growing epidemic in the county even if they don’t detect it.”

That could spell trouble for the state’s small towns and rural areas, where even a single reported case means that the virus could already be spreading.

On March 13, President Donald Trump declared the outbreak a national emergency and announced a government partnership with the medical lab industry to greatly expand testing. It was to be a rescue mission of sorts, tapping the infrastructure and expertise of the private sector to streamline the process and stave off critics who complained not nearly enough people were being tested.

A week later, Houston followed other cities around the country and opened its first drive-thru testing site at Butler Stadium, reserved initially for first responders and health care workers with a promise to expand to others who were showing symptoms or considered high risk.

A second city site was opened recently, bringing the total in the area to four, including two Harris County sites. The total testing volume for all four was originally capped at 1,000 people per day. Meanwhile, hospitals, clinics and doctors’ offices forged their own agreements with private labs or created their own tests.

Almost immediately, demand outstripped resources at every step of the process. Lines at testing sites snaked for miles, testing supplies and the tests themselves grew scarce as did the protective gear needed to safely administer them. The wait for results went from a few days to up to two weeks. Meanwhile, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance has continued to shift, leading to even more confusion and delays.

Quest Diagnostics, one of the two major commercial labs that won a government testing contract, said in late March it had a backlog of 160,000 tests as its labs were overwhelmed. Since then the company has said its backlog has been cut in half.

LabCorp, the other major lab, said in an emailed statement Saturday it “continues to do everything it can to ensure that healthcare providers and patients receive their test results as quickly as possible.” The company acknowledged that in the early days some results took longer than anticipated but more recently the turnaround after picking up a specimen is usually two to four days.

Other players are now entering the marketplace, with a spate of new rapid-return testing options soon to be available that come with promises to boost the number of tests given and processed. But roll out remains spotty and a timeline unclear.

At Legacy Community Health, a network of clinics that serve Houston’s poor and uninsured, the number of people being tested has shrunk dramatically. When testing began there March 16, as many as 160 people per day across 15 clinics could be tested. Today, at best, only 30 a day are tested, said Dr. Vian Nguyen, chief medical officer at Legacy.

When testing launched, anyone with symptoms plus exposure to someone with the virus or who traveled could get a test at Legacy, she said. But as the system bogged down and supplies became tight, testing criteria became limited to health care workers and first responders, followed by high-risk patients who were exhibiting symptoms – leaving countless people, many who were also sick, shut out.

“It is clear that supply chain issues are driving our testing criteria and access to testing sites, rather than the need for clinical assessment and data collection,” said Nguyen, adding that the criteria could broaden as more supplies become available.

She and others say a more realistic option, especially amid talk of reopening businesses, is a pivot toward antibody testing to detect if a person has developed a resistance to the virus. While unknown if once infected a person can get covid-19 again, the presumption is they would be at least partly protected.

“As a doctor I have no idea where to tell my patients to go to get tested,” said Dr. Marrie Richards, a Houston family practitioner.

One of her patients, a restaurant worker in his 40s who was clearly sick, went to a testing site in Katy on March 31 and waited in his car six hours. The location closed before he reached the front of the line. Richards said he returned the next day, arriving an hour before it opened, and waited two more hours before finally being tested. His results came back positive.

Richards scoffs at the idea that most people who are ill will wait nine hours for testing. They will just never know, she says. Nor will they be counted.

Two negatives, one positive

Back before things got really bad, before the city shut down, Courtney Scobie got her hair cut.

The 42-year-old wrestled mightily with whether to keep her appointment on March 18. The rodeo had been cancelled and schools had just been closed, but like many in Houston at the time, she was not sure of her risk. She decided to proceed with caution: the salon would be mostly empty, her hairdresser had sanitized his station thoroughly, and they skipped their usual hug.

Four days later, on Sunday, March 22, she got a text from him asking to call immediately. She knew. And started to cry.

Her hairdresser, who during their appointment had no idea he was infected, had just tested positive. He thinks he picked up the virus from a client before Scobie, who was also asymptomatic at the time but was later hospitalized.

Mostly she was mad at herself. “Why did I have to go do that?” she thought, “I felt really dumb. I felt really guilty that I could expose my family.” Later that night her fever kicked in.

She called several doctors who told her she was ineligible for testing because she did not have an underlying health issue. She was to quarantine and assume she had the virus. On March 25, her husband found a physician who tested her for $60 for the office visit plus $125 for the test. The next day she learned she tested positive.

Forty-eight hours later, her husband, Bruce Scobie, who has a history of asthma, began coughing. On March 28, he was tested at an urgent care clinic. The next day he was in the emergency room with shortness of breath but released. A few days later his test came back negative.

Scobie’s husband has since been tested twice more by the same physician who tested Scobie. The doctor’s idea was to try to compare results because so many did not make sense. Out of his three tests, two were negative, one positive.

Public health experts now warn that the typical swab tests can have up to a 30 percent false negative rate, depending on how they are administered.

Tuesday morning, just after 4:30 a.m., Bruce Scobie could not breathe. He was taken by ambulance to Memorial Hermann Southwest and admitted. Doctors suspect pneumonia linked to COVID-19.

Nowhere in the numbers

Marci Rosenberg has no idea how her family became exposed to the virus. The best guess is it happened sometime in February when she and her 15-year-old daughter, Mimi, went to New York City. The teenager was the first to get sick, diagnosed with a bronchial infection and given antibiotics which did not fully work. She seemed to get better briefly but then fell ill again.

The first time Rosenberg asked for a test for Mimi was in late February, back when the virus had landed hard in other parts of the world but had yet to find a foothold in the U.S. “They looked at me like I was crazy,” she said. The first confirmed case in New York was March 1. The incubation period for the virus can be up to 14 days.

In the coming weeks there would be five more attempts for either Mimi, herself, or for her husband, Ben Samuels. The couple’s son, Ethan, also soon became ill. There is little doubt, Rosenberg’s doctor said, that they all have covid-19 although only one was tested.

“It’s certain that me, my daughter and my son are nowhere in the numbers,” said Samuels, “And we’re not certain Marci is either.”

After her positive result the couple scoured reports of confirmed cases, which only listed basic demographic information. Rosenberg is 52. In the immediate time surrounding her test, there was only one woman in the 50 to 59 age range but unlike Rosenberg that woman was listed as hospitalized.

Further, the couple was told a public health official would call to begin the process known as contact tracing to track down those who they might have infected. To this day no one has called them, they said. So, instead they began their own backtracking, warning roughly 30 people they may have exposed.

In a seven-block radius at least eight people the family had contact with are now or have been sick recently. Only one was tested, which came back negative. So none will show up in the city’s count.

“Of course there is an undercount,” said Samuels, who added his family is now slowly on the mend. “The numbers you hear are totally useless.”

Staff writer John Tedesco contributed.

twitter.com/jenny_deam

Comments are closed.